The world’s markets, your way.

The Finalto Difference

Finalto is an award-winning financial services provider specialising in liquidity, risk management and world-class financial technology. Through our deep expertise and advanced technology, we offer customised solutions that connect our clients to global markets, seamlessly.

We deliver best-in-class liquidity, execution and prime broker solutions across multiple asset classes cross-margined on a single account.

We’re Trusted

An award-winning global provider

We’re Trusted

An award-winning global provider

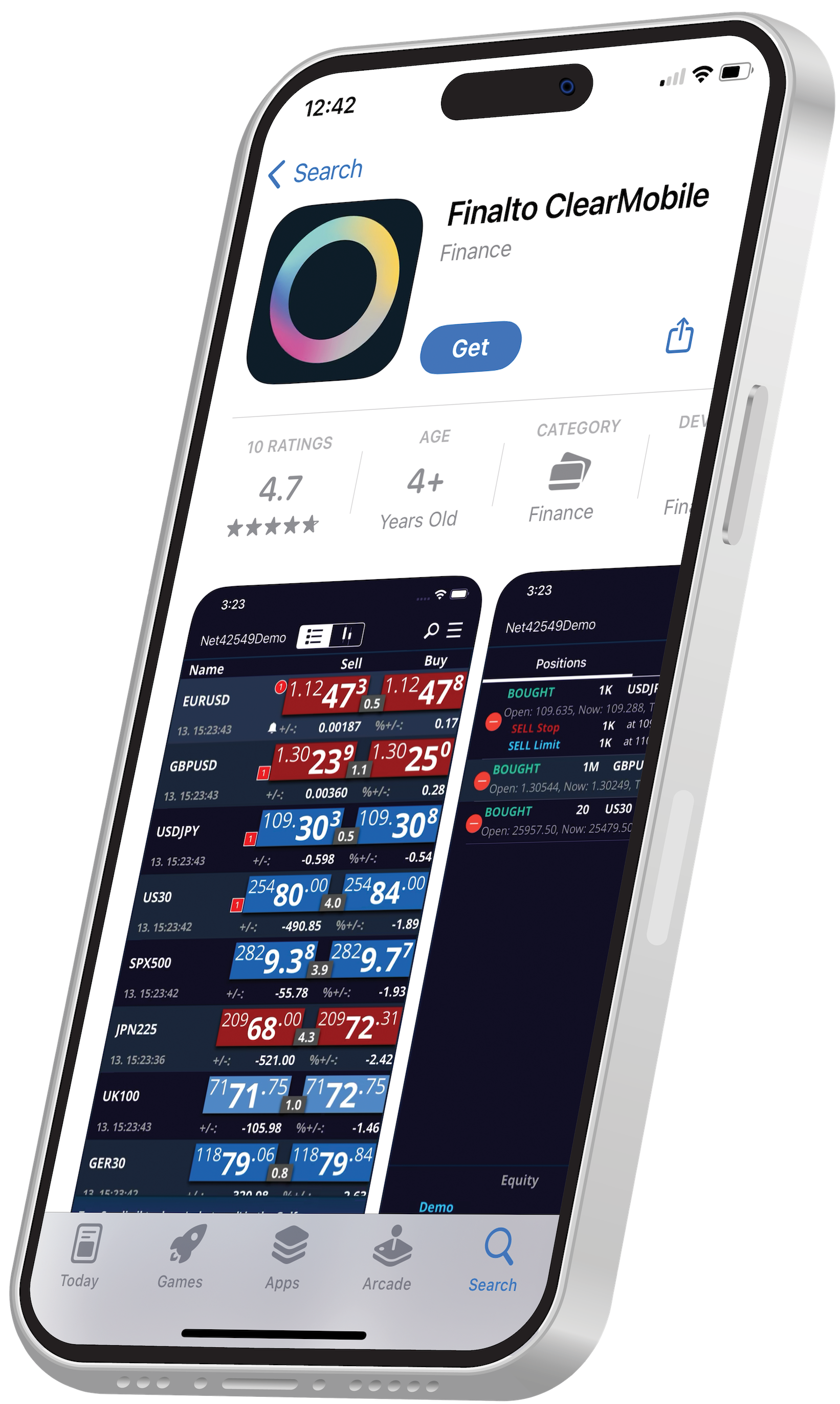

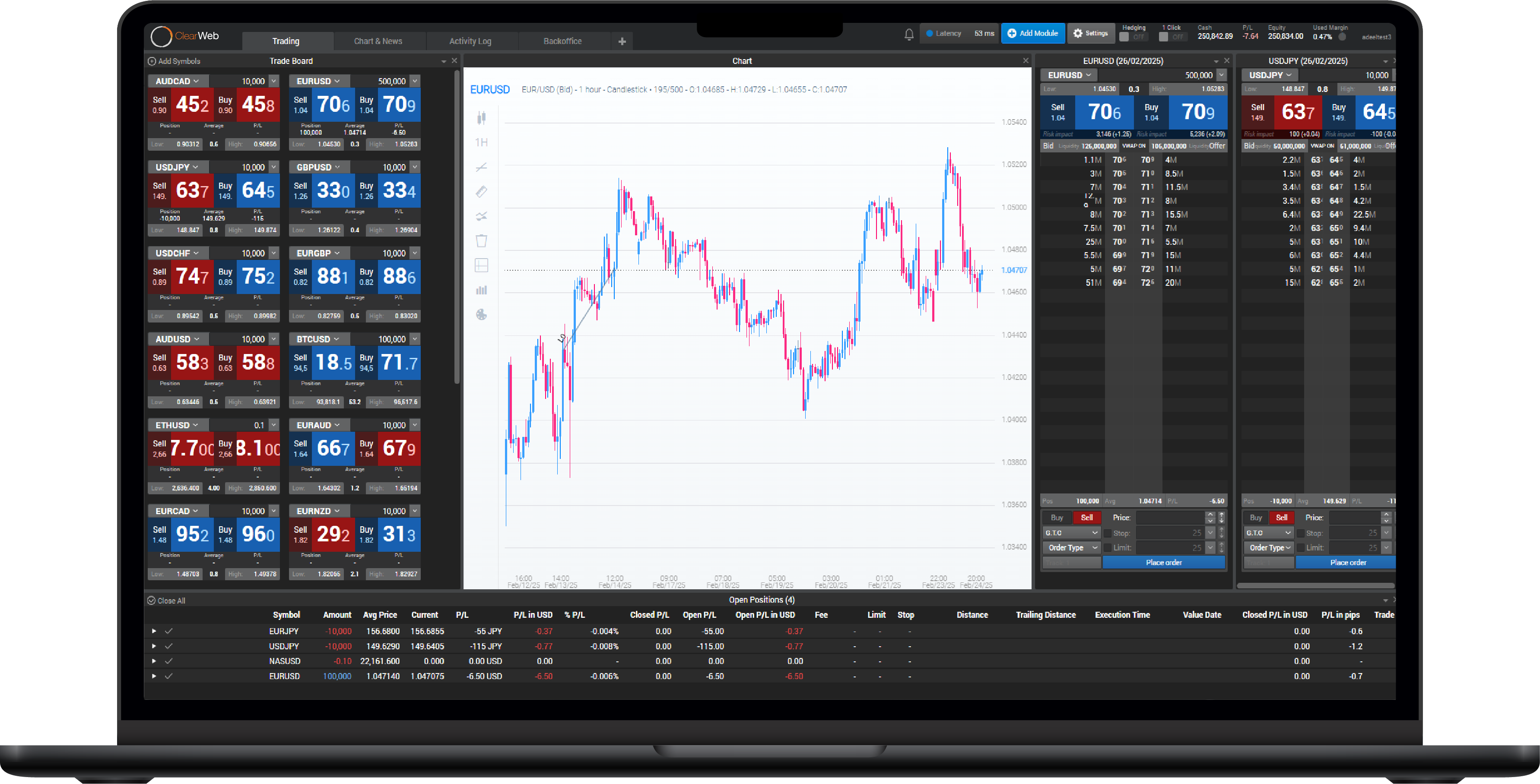

Finalto’s Technology

Financial software that supports your business strategy.

Our in-house development team is continually refining Finalto’s integrated award-winning fintech platforms, including ClearPro, ClearWeb, ClearMobile and FIX Connectivity.

Finalto’s Technology

Financial software that supports your business strategy.

Our in-house development team is continually refining Finalto’s integrated award-winning fintech platforms, including ClearPro, ClearWeb, ClearMobile and FIX Connectivity.

Get in Touch

marketing@finalto.com

Telephone: +44 (0) 203 4558 750

Fill in the contact us form and we’ll be in touch.